To Make the World Again

Common Sense at 250

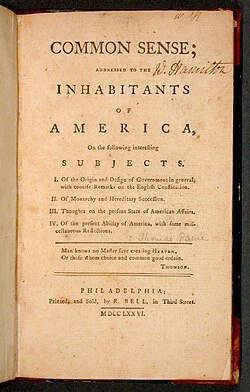

On January 10, 1776[1], Robert Bell printed a small, forty-six-page pamphlet and advertised it in the local Philadelphia newspapers. Common Sense became an instant hit, selling over 120,000 copies in just three months. Thomas Paine’s simple, powerful language persuaded many Americans to support independence and offers a clarion call and guiding light to our nation as it prepares to celebrate its 250th birthday.

In early 1776, the Revolutionary War had been raging for eight months. The Continental Congress had created an army the previous summer and appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief. Yet, the colonies were still a part of the British Empire and many citizens held out hope that reconciliation with King George III was possible and preferable to independence.

Paine rejected this timidity with two well-known arguments. First, he offered a careful exposition about the purpose of government, writing that “even in its best state, [government] is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one.” Second, he offered a meticulous take-down of monarchy, arguing that “all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever.” Even the best men, who “might deserve some decent degree of honours” could have descendants “far too unworthy to inherit them.” Critically, Paine wrote of the equality of men six months before the Declaration of Independence made those words famous.

Paine also offered an argument about monarchy that has not received as much attention over the last two decades but remains more relevant today than ever. He wrote that the monarchy was ridiculous because “it first excludes a man from the means of information yet empowers him to act in cases where the highest judgment is required.” The king was set apart from his people, yet he was expected to rule on their behalf.

King George III and his fellow monarchs were isolated from information because they rejected criticism. Freedom of speech did not exist in eighteenth-century Britain. Speech critical of the king was not a difference of political opinion—it was disloyal or treasonous. Paine had witnessed firsthand writers arrested and jailed for publishing anti-government material in England before he immigrated to Philadelphia in 1774. Accordingly, he published Common Sense anonymously.

Paine’s revolutionary contemporaries, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Washington, and John Adams, understood the limitations on their speech. This context explains the widespread demands for a bill of rights in the new Constitution and inspired the protection for speech in the First Amendment.

The First Amendment’s protections have been imperfectly applied since its ratification, of course. The United States government shuttered pro-Confederacy newspapers during the Civil War and censored mail during World War II. Congress has passed several versions of sedition laws, first in 1798 to target Democratic-Republican editors and again during World War I. Under Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, the government arrested those that criticized the administration, the flag, the Constitution, or the military. After the war, the Palmer Raids continued with widespread arrests and deportations of socialists, communists, and anarchists—especially if they were immigrants.

Free speech is under attack again today. The government has targeted comedians, political opponents, and law firms that represent critics. Media companies have offered payment to the president to avoid lawsuits or pulled stories that might jeopardize mergers. Just this week, the administration announced it was demoting Senator/Captain Mark Kelly and issuing a formal censure letter of a video it didn’t like. Many critics have gone silent to avoid retribution.

And yet, free speech remains as essential to the future of the republic as it was when Paine wrote Common Sense. Presidents are not kings, but they wield enormous power. Their task is a nearly impossible one. They must make incredibly difficult decisions on behalf of the 300 million Americans they represent. No one person can have all the answers. Information, and critical speech, is essential to their job.

The best presidents (and leaders of any stripe) understand that the job has a tendency to silo them. Diverse and conflicting information can be hard to acquire. They surround themselves with people who will tell them “no” and will disagree with each other. George Washington pleaded with Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson to stay in the cabinet so that he would have both perspectives represented. That is what the best do, even when it is uncomfortable.

Paine offered a solution for both 1776 and today. “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he urged his fellow Americans. They listened—and created the first nation based on an idea. A republic is inherently an opportunity to make the world again, each day, each generation. We decide our world. Let’s make it a good one.

[1] There is some debate about whether the publication date was January 9 or 10, 1776, but most sources seem to settle on January 10.