The Voting Rights Act, 60 Years Later

August 2025 Imperfect Union

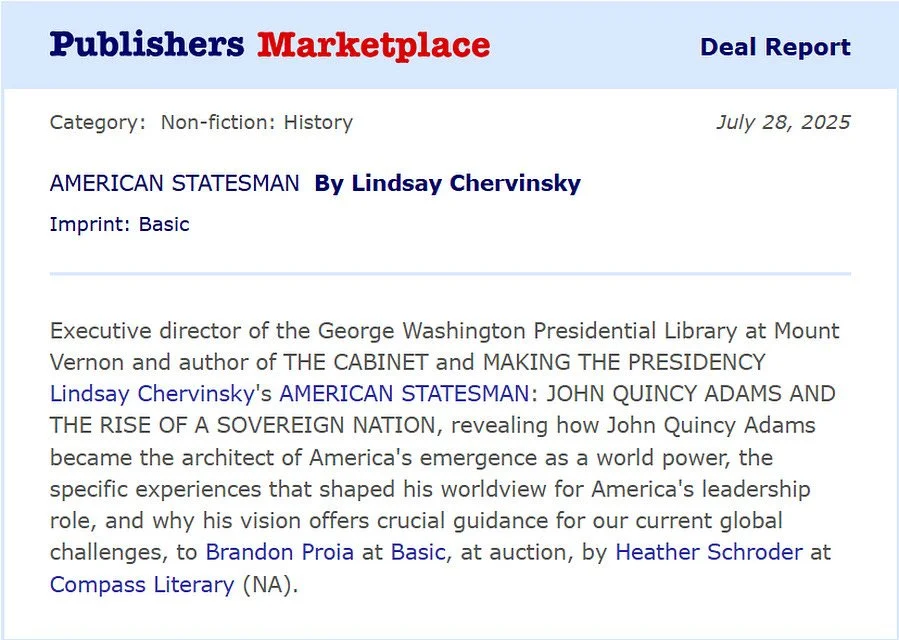

Before I get down to business, I wanted to share some fun news. If you follow me on social media, you probably saw this announcement, but if not: my next book is coming!

I still have to write the thing, but I’m very excited about it. Get ready for lots of JQA!

Down to business. I read somewhere in a book that only 13% of people living in the thirteen states could vote in the 1789 election. Of course, I can’t remember which book, but it obviously stuck with me. The number makes sense when you consider that most white women, people of color, Native Americans, and poor white men were denied suffrage. Many states retained property requirements until the 1820s.

From the founding to today, therefore, voting rights have *mostly* been on an uphill trajectory with a few notable setbacks. I’m going to quickly walk through the timeline before diving into twentieth-century legislation in more detail.

1856: North Carolina became the last state to remove the property requirement for white men to vote.

1868: The 14th Amendment was ratified. It is multifaceted and complex, but for the purpose of this conversation on voting rights, the amendment guaranteed citizenship to anyone born in the United States (with a few minor exceptions) and prohibited the states from passing laws that abridged “the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

1870: The 15th Amendment was ratified. It declares that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Critically, the 15th Amendment also gives Congress the right to pass legislation to enforce this right, which negated claims of congressional overreach.

In between the 15th Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many states passed laws, known as Jim Crow laws, that prevented most Black men and women from voting. While the laws did not explicitly bar voting based on race, they included terms that de facto eliminated voting. For example, some states required proof that your grandfather could vote. If your grandfather was enslaved, that was obviously impossible. Other states imposed literacy or “civics” tests with impossibly hard questions that white voters were not expected to answer.

These laws were backed up with brutal intimidation campaigns, widespread violence, and lynching.

Congress also passed several other laws and the Supreme Court issued decisions during this period prohibiting other minorities from voting and gaining full citizenship, including the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and Takao Ozawa v. United States in 1922.

1920: The 19th Amendment was ratified and extended suffrage to white women (in practice). Although the amendment did not specify race, Jim Crow laws effectively restricted the amendment’s reach to white women.

1957: Civil Rights Act was passed and signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This bill “established the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights for two years, created a civil rights division in the U.S. Justice Department, and authorized the U.S. Attorney General to seek federal court injunctions to protect the voting rights of African Americans.” It was limited in its scope and weakened by Democratic Party attacks, but it was a notable step forward. It was the first civil rights legislation since 1875 and marked a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. It showed that progress could be made, even if imperfectly and incrementally. The first step can often be the hardest, as it puts a crack in the dam. The Civil Rights division at the DOJ also went on to play a critical role in future civil rights protections.

1965: The Voting Rights Act was passed and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. It is lengthy and full of important provisions, which can broadly be categorized into two groups: general provisions, which apply to the entire country, and special provisions, which apply to certain states and local governments.

A few notable elements. Section 2 prohibits any “voting qualification or prerequisite” that results in the denial of voting based on race, color, or language minority status. This includes both laws that have discriminatory intent and those that result in the denial or abridgment of the right to vote based on color.

Section 2 recognizes two ways in which the right to vote is abridged: the denial of the right to vote and through “vote dilution,” which is when the strength or effectiveness of the vote is reduced. More on that in a minute.

Sections 3-5 include specific provisions that determine which states and local jurisdictions are subject to additional oversight. Section 5 requires these jurisdictions to gain “pre-clearance” of new voting rights laws if they had a history of voter discrimination to ensure the new statute did not have discriminatory effect. Initially, this pre-clearance coverage primarily applied to states in the Deep South, but other jurisdictions were added over time, including local governments, sections of California, Alaska, Connecticut, and the full states of Arkansas and New Mexico.

2013: In Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court ruled the pre-clearance requirement of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional because the coverage formula was out of date, and therefore violated the principle of equal state sovereignty.

Why It Matters Today: In June, the Court ordered a rehearing of Louisiana v. Callais this fall. This case involves a challenge to Louisiana’s congressional district map. The plaintiff “claimed that this new map violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by prioritizing race in its creation” of a second minority-majority district.

Let me take a quick step backward. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act prohibited racial gerrymandering for the purpose of “vote dilution.” This section was strengthened in 1982, when President Reagan signed amendments into law. Notably, this bill was bipartisan and passed with strong support from southern congressmen.

In 1986, the Supreme Court established a test for these districts, known as the Gingles test (named after the case Thornburg v. Gingles). The test requires three conditions for minority-majority districts:

The racial or language minority group "sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district";

The minority group is "politically cohesive" (meaning its members tend to vote similarly); and

The "majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it ... usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidate." Meaning white voters (or whatever majority exists) vote against the preferred candidate.

These factors combine to produce a relatively stringent test. For example, in the 2024 election, minority and majority voters moved away from traditional race-based voting blocs. Similarly, geographic segregation of voters is declining, making it harder (at least in some states) to find “politically cohesive” regions of minority voters.

Notably, the Gingles case upheld that vote dilution is a violation of the Voting Rights Act, even without discriminatory intent. To learn more, check out this podcast episode from the National Constitution Center.

The Louisiana v. Callais case is complicated because it involves several different racial gerrymandering questions, including whether race should be the primary factor when considering districts and therefore, what level of scrutiny the court should apply to its review. I think a full explanation of that case might tip this post over the edge. So, a few resources.

This primer from the League of Women Voters is really helpful.

This post from Steve Vladeck over at One First talked about the case in 2024 when it first came up.

What you need to know at this moment, however, is that the Supreme Court has steadily chipped away at the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1985 since about 2010. I leave it up to you to decide whether that’s the appropriate call or not, and the podcast I linked above includes both sides of the argument. This case is another opportunity to alter the voting rights legislation and could have a huge impact on the gerrymandering/legislative representation map across the country. Voting rights and voting rights legislation is not a thing of the past, it is very much present.