The President’s Awesome War Powers

July 2025 Imperfect Union

We often talk about the presidency being the most powerful office in the world, and it has only gotten stronger in the last century. War powers are one of the most expansive elements of the presidency. War powers have been in the news lately thanks to the strike on Iran, but this topic is actually evergreen. In the last several decades, both parties have discussed reforms to limit the president’s war power, but often fail to take action once in the majority. So, what are war powers? Where do they come from? How have they evolved in the last two hundred years? And how and when has Congress pushed back? Let’s dive in.

War powers refer to the federal government’s ability to use military might. Typically, these conversations and powers refer to the deployment of military force abroad. War powers are located in two places in the Constitution. Article I entrusts Congress with control of the army with the power,

“to declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;”

“To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;”

“To provide and maintain a Navy;”

“To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;”

Article II entrusts the president with command: “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.”

This division of responsibility was intentional. Monarchs typically control both the purse and the sword. That much power in one person’s hand is prone to abuse and misuse. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention divided the power to check that impulse and provide accountability.

In theory, the division of responsibility is clear. Congress declares war and the president manages it. But as history quickly demonstrated, there is a lot of grey area between war and peace. Technological advancement and the increasing messiness of warfare have added additional complications. Additionally, very few of the conflicts in American history have been called traditional wars as the framers envisioned. Let’s explore what that means.

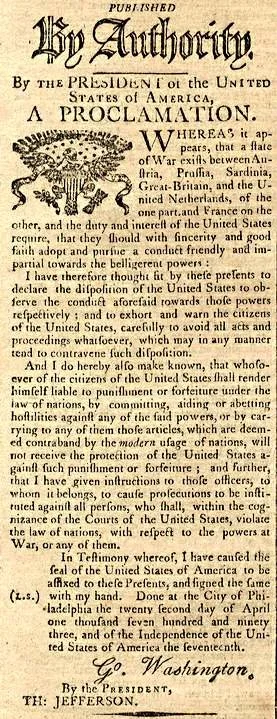

In February 1793, France declared war on Great Britain. The conflict quickly spiraled to engulf their allies, enemies, and colonies. President George Washington learned of the war in early April. The United States had signed the Treaty of Defense with France in 1778, obligating both nations to come to each other’s aid in the event they were attacked by their enemies. Washington had to determine if the treaty applied in this scenario, if the U.S. was obligated to go to war with Britain, or if neutrality was possible.

He had three options to resolve those questions: 1) wait for Congress to resume its session in November (Congress was out of session anytime anything interesting happened in Washington’s administration); 2) convene an emergency session of Congress; 3) work with the cabinet to manage the crisis.

On April 18, Washington sent a letter to the cabinet, outlining the questions he wished to discuss with the secretaries the next morning. The list of thirteen questions included,

“Shall a proclamation issue for the purpose of preventing interferences of the Citizens of the United States in the War between France & Great Britain &ca? Shall it contain a declaration of Neutrality or not? What shall it contain?”

“Are the United States obliged by good faith to consider the Treaties heretofore made with France as applying to the present Situation of the parties. May they either renounce them, or hold them suspended ’till the Government of France shall be established.” (King Louis XVI, who had signed the treaty on behalf of France, had been executed four months earlier.)

“Is it necessary or advisable to call together the two Houses of Congress with a view to the present posture of European Affairs? If it is, what should be the particular objects of such a call?”

Over the next five months, the cabinet met up to five times per week, for several hours per day to resolve the Neutrality Crisis. Washington and the cabinet pursued a three-step strategy. First, they issued a proclamation declaring the United States would remain friendly with all combatants. They notably avoided the word neutrality because it carried legal implications.

Second, they requested the recall of the French minister, Citizen Edmond Charles Genet, when he refused to respect their guidelines for neutral behavior on American territory and in American waters.

Third, they crafted a series of rules dictating the behavior of citizens and visitors during periods of neutrality. That fall, when Congress returned to Philadelphia, it codified those rules into law, which governed periods of neutrality through the 19th century.

How did this period affect war powers? The opposite of war is peace (or in this case neutrality). When Washington issued his proclamation, some law makers questioned whether he had the power to unilaterally decide the nation’s position. If Congress has the power to declare war, wouldn’t it follow that it also had the right to declare peace?

Representative James Madison wrote to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, confessing, “I must own my surprise that such a prerogative should have been exercised.” He acknowledged that he might have missed something in the Constitution (though I suspect he was being self-deprecating here, because both men knew how well the Madison understood the Constitution), before writing, “I have always supposed & still conceive, a proclamation on the subject could not properly go beyond a declaration of the fact that the U. S. were at war or peace.” The right to decide whether the country was at war or peace, “seems to be essentially & exclusively involved in the right vested in the Legislature,” Madison argued. In other words, only Congress had the right to change that status or make an active proclamation. “Did no such view of the subject present itself in the discussions of the Cabinet” he asked?

While some Democratic-Republicans grumbled about the proclamation and others demanded the nation support France in the conflict, Congress largely deferred to Washington’s handling of the crisis. In doing so, they tacitly approved that the president has the right to take decisive action in a diplomatic crisis. Washington carved out enormous jurisdiction for his successors when it came to foreign policy. Although he did not wage war or deploy military force in this moment, his precedent laid the groundwork for others to do so later.

The next key turning point for presidential war powers came during the Civil War. During the Mexican American War, Congress declared war, which made President Polk’s use of war powers fairly standard within the bounds of the Constitution, even if the war itself was manufactured.

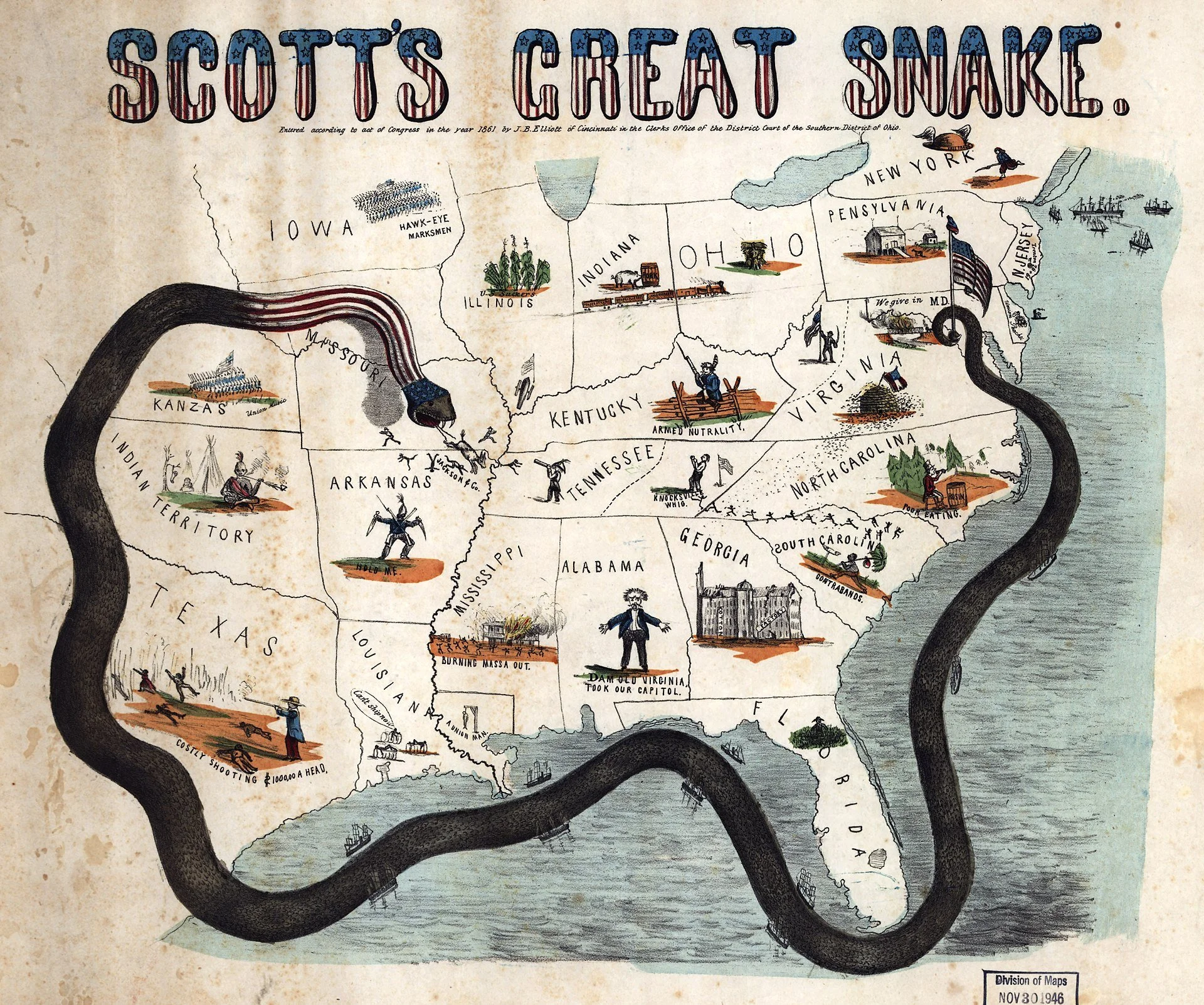

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. In February 1861, six states formed the Confederacy. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, a federal fort, officially beginning the Civil War. Congress was out of session. A few days later, Lincoln issued a proclamation summoning the militia in the northern states and convening an emergency session of Congress to begin on July 4. Before Congress could gather, Lincoln issued another proclamation implementing a naval blockade around the Confederacy and instructed General Winfield Scott to suspend habeas corpus in Maryland.

General Scott’s plan to crush the Confederacy through naval blockade. While the plan did not work in the short term, in the long term the naval blockade inflicted significant pain on the Confederacy’s economy.

Once Congress gathered, Lincoln explained his actions:

“It was with the deepest regret that the Executive found the duty of employing the war power in defense of the Government forced upon him. He could but perform this duty or surrender the existence of the Government.”

Congress evidently agreed, because it later passed laws authorizing the suspension of habeas corpus and use of military power after the fact. But a notable precedent had been established that when a crisis occurs, a president should ask forgiveness, rather than permission.

World War II marked another important milestone. On December 15, 1941, just a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of war, Congress passed the First War Powers Act, which empowered the president to reorganize the defense departments for maximum efficiency and permitted censorship of the mail for the war effort. Critically, this act was designed to expire six months after the end of the war. Three months later, Congress passed another war powers act, giving the president authority to acquire land for military purposes and establishing procedures for war contracting. While Japanese Internment was one the most notable use of executive power in World War II, it was justified under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. Read more about the Alien Enemies Act here.

The Korean War was the first major conflict in which Congress utterly abdicated its power to authorize war. On June 25, 1950, President Truman consulted with congressional leadership when he first sent supplies to South Korean forces. The next day, he offered air and naval support, and Congress voiced no objection. On June 30, Truman committed American ground troops, but Congress elected not to interrupt its July 4th recess by summoning its members back to an emergency session. Their silence largely reflected bipartisan support for the president’s actions, not realizing they were setting a dangerous precedent for what would come next.

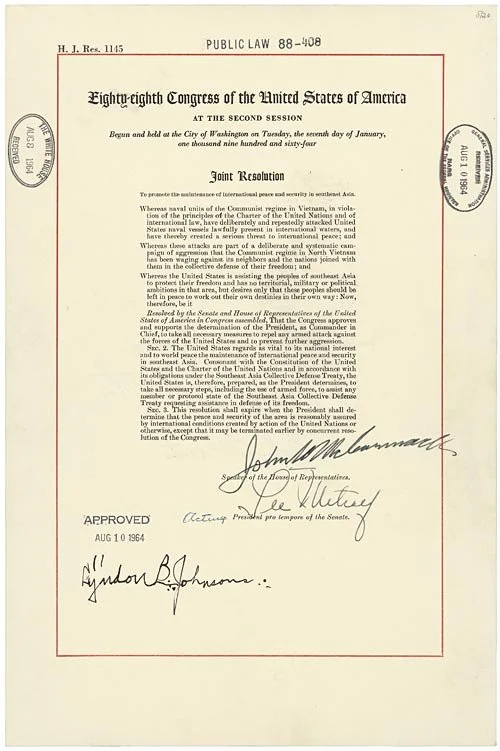

In early August 1964, two US destroyers stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin reported that they had been fired upon by North Vietnamese forces. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorized President Johnson to take measures “to retaliate and to promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia.” The resolution was broadly defined and used by President Johnson and Nixon to fight in the Vietnam War. This type of resolution cannot be separated from the general and pervasive concern about the threat of communism. Supporters argued that presidential action was justified by the need to prevent the falling “dominoes” of states to Communist regimes, starting with China and Korea. In retrospect, this argument seems a bit hyperbolic to us, but at the time it was pretty consuming.

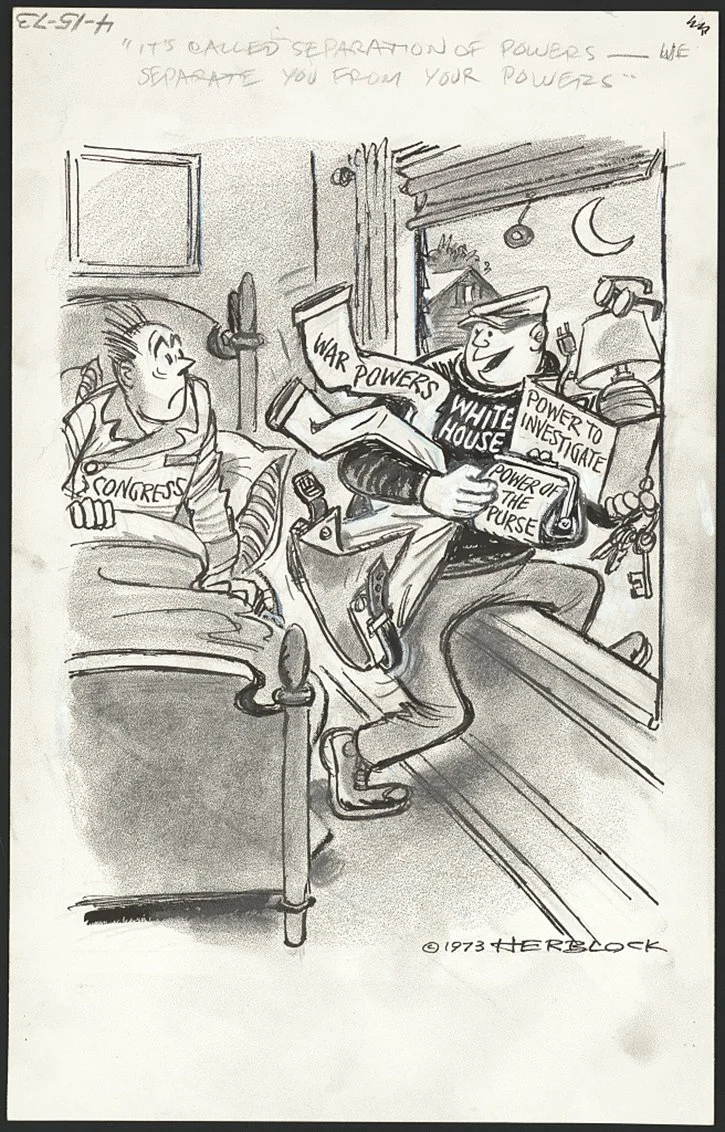

Nine years later, Congress clawed back some of that power in the War Powers Resolution of 1973, when Nixon ordered bombings in Cambodia without notifying Congress. The bill “required the President to consult Congress before the start of hostilities, and report regularly on the deployment of US troops.” It was designed “to fulfill the intent of the framers of the Constitution” and guarantee “that the collective judgment of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities.” Nixon vetoed the bill and Congress overrode the veto, which required a significant bipartisan vote.

Library of Congress

After the War Powers Resolution of 1973, there was a general trend toward congressional oversight. Not perfectly, of course, but my sense is that Congress was eager to avoid the mistakes of the Vietnam War. Then the terrorist attacks on 9/11 changed everything again. Three days after the attacks, Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, which allowed the president “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States.”

The AUMF was an enormous grant of war powers to the president with no expiration date. Presidents from both parties have used the AUMF to justify military missions and troop deployments. The AUMF remains in effect today.

There have been several attempts to reform the president’s war powers in the last five decades. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 was the first big attempt. Since then, presidents have stepped up their reporting of use of force. But it has also spawned a battle over what “start of hostilities” means. Is it troops on the ground? Is it drones? Is it bombs? All valid questions with no clear answers.

In 2021, Senator Chris Murphy (D) aligned with Senators Mike Lee (R) and Bernie Sanders (I) to introduce a new National Security Powers Act to limit the president’s authority. Although the sponsors were bipartisan, the bill went nowhere. Last month, Rep. Thomas Massie introduced a bill to limited the president’s power to engage in hostilities in Iran.

The challenge, thus far, is that the party in power (with a few exceptions) rarely wants to limit its own authority and flexibility. And in this era of nasty partisan politics, few presidents want to subject themselves to congressional oversight, which is not always conducted in good faith.

The other challenge is the ongoing evolution of warfare. I am not a warfare expert and have never worn a uniform, so I’m going to limit my remarks, but I think it’s clear that drones will at least alter strategy. I know this ending is a bit ambiguous, but you know how I like to avoid predictions. The stalled debate over war powers is consistent with many of the challenges of our current political system. Congress clearly has the power to do something about war powers, it just needs to exercise its oversight authority. We have three branches for a reason.

Disclaimer: I want to be super clear, as I always try to be when I am writing about legal matters, I am not a lawyer and I do not pretend to be on television or in my newsletter. Which is why you will see my citations are always to well-respected sources. I also try not to get out over my skis and stick to the historical analysis. That being said, the Constitution does not just apply to lawyers and judges. I have so much respect for legal analysis and much love for many lawyers (including those in my life), but I think all citizens have the duty to read and to try to comprehend the Constitution and the laws that will affect their nation. Some provisions and clauses are complicated, and the interpretations require legal knowledge. But if history is any indication, legal interpretations change over time; they are not gospel. So, ask questions! Read analysis. And don’t cede the Constitution to one profession.