The History (and Rejection) of Military Parades

June 2025 Imperfect Union

On October 23, 1789, President George Washington traveled north to Boston. In his first term, Washington visited every state. He toured one side of the state and returned down the other side. He stopped in local towns, visited mills and ports, attended multiple religious services of different denominations every Sunday, and dined with leading citizens.

Washington’s tours had two purposes. First, he wanted to see the diversity of American life. In 1789, just as today, there were limitless ways to be an American. Washington used his tours to broaden his visibility into the daily lives of American citizens. Second, few Americans interacted with the federal government. The flag did not yet have emotional significance and the emotional bonds between the people and government were fledgling and fragile. Washington’s visit strengthened them.

As Washington stopped outside of Worcester, Massachusetts, he received word that the local militia planned to parade and demonstrate for him. He declined to participate. “I conceived there was an impropriety in my reviewing the Militia, or seeing them perform Manoeuvres,” he noted in his diary. As a “private Man, I could do no more than pass along the line,” Washington wrote to the local commander.

Washington drew a critical distinction with this refusal. As Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army (which was created 250 years ago yesterday!), he had regularly participated in parades and reviews. Later in his presidency, when gathering the militia for action, he gathered them for review. But at that moment, the nation wasn’t at war. There was no insurrection, no need for armed force. He was a civilian commander. The parade would be inappropriate.

Washington’s rejection of the parade was consistent with his war-time behavior and relentless deference to civilian authority. He was conspicuously respectful of Congress for the duration of the war, even when they didn’t deserve it. Few congressmen understood the sacrifices of the army and how the legislature’s inability to raise money undermined the army’s survival. And yet, Washington always deferred to civilian authority.

This deference was put to the test at the end of the war. Most soldiers and much of the officer corps hadn’t been paid in years. Some officers began whispering about ways they might use military force to encourage Congress to cough up their back pay. In a spectacular display of strategic theatrics, Washington neutered the threat of military coup and put to bed any future grumblings. (I’m thinking that might be a good subject for more in-depth exploration for a future newsletter).

Of course, Washington’s ultimate gesture of subordination to civilian authority was his decision to return his commission and not seize power. We tend to assume that of course history would unfold that way, but in the age of monarchs and kings, it was a revolutionary act.

Most presidents have taken Washington’s precedent as gospel. The military has several rules and regulations to keep armed forces out of politics. To my knowledge, however, there is very little written down that limits presidential behavior toward the military (outside of actually deploying force, which is more regulated). Most of it is based on norm and custom, which almost all started with Washington.

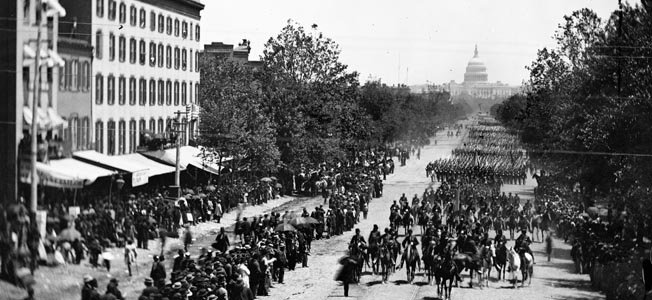

Despite Washington’s precedent, we have had military parades. But they are almost always when we are sending troops off to battle or celebrating a victory. New York City has been the site of several celebrations, including this review of the Union forces after victory in 1865.

Grand Review of 1865

New York City hosted a celebration after World War I as well. This parade was a bit of a mess. The Times wrote that “dozens of artillery tractors took a wrong turn after the event and got lost in Brooklyn for hours.” Not your average Brooklyn afternoon.

Parade of the 77th Division, 1919. Underwood & Underwood. Mayor’s Reception Committee, NYC Municipal Archives.

Because the war in Europe was already raging when the U.S. entered World War II, the country held parades to send troops off to battle.

Parade to cheer on naval units marching on Fifth Avenue in a war parade in New York, June 13, 1942. (AP Photo, File)

In World War II, American forces held parades when they liberated Paris, as well as in the United States. The New York celebration included thousands of members of the Army's 82nd Airborne Division, tanks and howitzers, closed the Manhattan Bridge, and brought heavy equipment over the East River from Brooklyn. The New York Times reported millions of spectators attended the parade.

U.S. soldiers march down the Champs-Elysees in Paris during the Victory Parade, Aug. 29, 1944. Department of Defense.

Most recently, we held a military parade in 1991 to celebrate the victory in the first Gulf War, though it was scaled down compared to the parades after both world wars. Washington, D.C. is usually the location for the official end-of-war parade. The parades typically start at the U.S. Capitol—the seat of the people’s power—and march past the White House and out of the city. The parades usually end at Arlington Cemetery to pay homage to the soldiers lost in battle. It is a symbolic gesture of the military disbanding and returning the power to the people.

So why does this history matter? In the 1950s, the Soviet Union regularly put on massive military parades to show off its strength. During the Cold War, several inaugural parades included the newest military technology. Accordingly, some aides in the White House approached Eisenhower about staging an expanded parade in DC to upstage the Soviets. He replied,

“to have a military parade without the end of a war or an inaugural or some big reason in Washington, D.C., that is out of our tradition.”

He was right. There are two fundamental characteristics that define our republic: the peaceful transfer of power and civilian control of the military. A military parade to honor something other than victory in war or as part of celebration of the peaceful transfer of power undermines the second characteristic. Will it end the republic? No. But republics rarely end in one giant explosion. There are a thousand tiny steps and then a collapse all at once.

Our republic depends on our norms and customs to survive. Most of our political practices and institutions are not maintained by force. They depend on citizens to uphold them and guarantee their future existence. The norms established 250 years ago are worth upholding—and as we enter this season of anniversaries—celebrating.