The Presidents and the Press — 2

November 2025 Imperfect Union

Theodore Roosevelt coined the term “bully pulpit” to refer to the president’s powerful platform and ability to influence public opinion. He regularly used the term “bully” to mean terrific or great, which is not necessarily how we think of the term today. Most people probably think of the president’s ability to control, influence, or shape behavior through the unparalleled powers of the presidency, perhaps in a slightly more menacing way that TR intended.

Both descriptions are apt and get at the heart of the relationship between the presidents and the press in the twentieth century. Presidents had enormous influence because the press covered their actions and statements more than anyone else. Now, the press did so because the office was the most powerful in the country (and eventually the world), but the relationship is symbiotic.

We ended part one discussing party presses and their relationship to presidents. The relationship between presidents and the press shifted dramatically toward the end of the nineteenth century with the rise of muckraker journalism. Muckraker journalism was some of the earliest investigative reporting that revealed the horrors of child labor, living conditions in slums, the disgusting quality in food factories, business consolidation, and political corruption. This new generation of reporters and photographers helped spearhead the Progressive Movement and produced reform including safer living conditions, child labor laws, food safety laws, and environmental protection. They also advocated for journalism as a profession and developed ethical standards, training, and education. The trusted journalists of the twentieth century—Edward Murrow and Walter Cronkite for example—were a product of this new profession.

The new standards of journalism inherently shifted the dynamic between presidents and the press. In the nineteenth century, opposition newspapers criticized the president and tried to uncover scandal. In the twentieth century, there were fewer party newspapers and in theory every journalist was looking for a story. In practice, it was slightly more complicated.

Many presidents managed to develop extremely cordial and mutually beneficial relationships with the press. No one was better than TR. In 1902, he created a press office in part of the newly-constructed West Wing. He instructed his cabinet secretaries to funnel all press requests through his private secretary so he could control access to news. But then he also put on a show. He invited reporters into the White House every morning while he was having a shave. He told stories and swapped bits of information with the reporters, who adored his jovial manner and constant energy.

The president also drove them crazy, and the feeling was mutual. After regaling them with the juiciest updates, TR would often tell them those stories were off the record and not for print. If they disobeyed, he banned them from the briefings. In return, the press asked questions designed to irritate the president, which inevitably provoked him into leaping up in outrage. They timed the most infuriating questions for the moment the barber was dragging the blade just under TR’s Adam’s apple, forcing the barber to quickly whip the blade out of the way or risk decapitating the president when he bolted out of the chair.

Despite the intentional provocations on both sides, the relationship was quite productive because each side understand the value of the other. TR wanted coverage and good photographs and cultivated relationships to make it happen. The press wanted continuing access to stories and information and played ball.

Another Roosevelt, this time, Franklin D. Roosevelt, managed a similarly warm relationship with the press. He brought reporters into the Oval Office for lengthy conversations and hosted annual press receptions. FDR had a knack for talking for a long time, making people feel seen and heard, and then once they left, they realized he hadn’t said much of anything at all. He knew just when to impart important information to keep them coming back, but mostly relied on his charm to keep them in line. He was aided in this endeavor in two ways. First, Eleanor Roosevelt also held regular press conferences for women reporters because they were not permitted in the regular press pool. Second, FDR spoke directly to the American people through his radio addresses. Newspapers were still the primary form of news consumption, but the rise of the radio made it easier for FDR to go around journalists from time to time.

In return, the press pool at the White House mostly kept quiet that FDR was in a wheelchair. This silence was partly a “gentleman’s agreement.” They didn’t take pictures of the president in the wheelchair to retain access to the White House, but there was a collective silence around disability. Society still sometimes viewed disability as a personal weakness, so it was not discussed publicly.

FDR was not the last president to benefit from press silence. John F. Kennedy’s numerous affairs were well-known among the press corps, but they were reluctant to publish stories about a popular president. That seems hard for us to imagine today, because we have a culture that relishes tearing down the popular, but I think that is partially a post-Watergate phenomenon. The Kennedy family was so popular, and First Lady Jackie Kennedy seemed so lovely and poised, that the press was reluctant to tarnish that image. The press corps was also almost entirely male and definitely had an “old boys club” vibe to it, so I suspect they were willing to cover for a president they saw as one of their own. I should acknowledge that there are some rumors that government agencies worked to suppress stories of affairs, but I haven’t found much hard evidence to corroborate.

For all the moments of glamour and cooperation, the relationship between the presidents and the press hit all-time lows during moments of national crisis. Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt all oversaw crackdowns of civil liberties during moments of war. During the Civil War, government agencies shut down the Chicago Times and the Sunday Chronicle in Washington, D.C. Lincoln ordered military tribunals for “Peace Democrats” who tried to thwart government efforts to recruit soldiers.

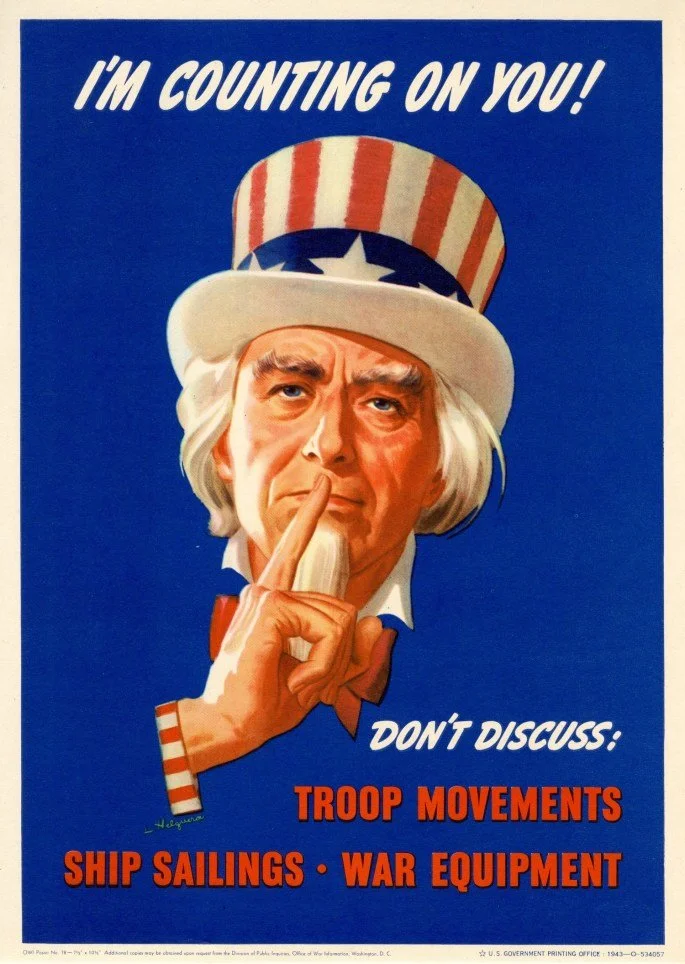

During World War II, the FDR administration deployed a two-pronged approach to information. They created an Office of War Information which produced pro-war and pro-US propaganda (which is not necessarily a bad thing in war) and the Office of Censorship which limited the spread of sensitive information to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

While we would accept neither the Civil War or WWII measures in normal times, most historians and experts seem to accept these restrictions on free speech and the press as understandable measures in genuine crises. The Civil War and WWII were the two moments when the nation’s future was most threatened and extraordinary measures were necessary. The same cannot be said for Wilson and World War I.

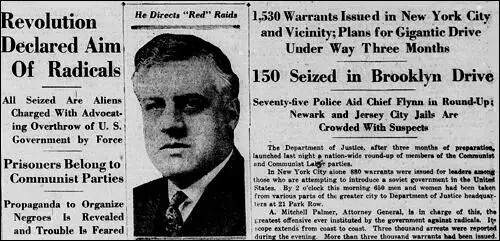

During WWI, the Wilson administration conducted widespread censorship of news and prosecuted dissenters under espionage and sedition acts. The laws were vaguely worded, broadly definitely, and led to thousands of prosecutions. In the aftermath of the war, the spread of communism led to a “Red Scare.” In response, the administration conducted warrantless raids, arrests, and deportations of suspected anarchists, communists, and radicals—many of whom were immigrants. These arrests and deportations became known as the Palmer Raids.

Wilson’s actions do not receive the same benefit of the doubt as Lincoln and FDR. Partially because WWI did not pose the same threat to American life (at least in retrospect) and because so many of the violations took place after the end of the war.

And of course, much ink has been spilled on Richard Nixon’s infamous relationship to the press. I’m not going to delve into it much here as there are so many good resources online. I found this 1973 New Yorker article absolutely fascinating, to see the history we’ve read so much about described in real time.

What’s important to know, however, is that Nixon started a new era of relationships between presidents and the press. Since then, few presidents have enjoyed their press coverage. They all complain they are treated unfairly, while the press always wants more access than it receives. Until this administration, recent presidents have begrudgingly accepted the press as an irritant that comes with the job. They gave interviews to networks they preferred and maybe tried to tweak access, but they mostly left the press corps alone. They respected the value of the fourth estate, even if they didn’t like it. We should expect and demand this approach from our leaders. Freedom of speech and the rights of the press are a canary in a coal mine. When they are attacked, they are often only the first.