The Presidents and the Press - 1

October 2025 Imperfect Union

Part 1: The Fourth Estate, the First Amendment, and George Washington

Hi friends – a couple of logistics first. Last month, I was traveling and dreadfully sick and completely forgot to include my usual notes about podcasts, events, etc. at the end. A reader commented on it, which really made my day because I wasn’t sure if you guys read those! I’ve included August and September, just in case you want to catch up.

Next, I started to write a piece about the presidents and the press, and it quickly became a massive behemoth. I thought it was important to include some historical context about the fourth estate and what that meant, as well as an explanation on the first amendment as that is so often misunderstood. This subject is an important one and I want to do it justice.

But as a result, we don’t even get to the first president for a bit. So, I’ve decided to break it into two parts. Part one, which you are reading now, ends just before Theodore Roosevelt. Part II, which will come out on November 1 (bonus newsletter!), will discuss the twentieth century, periods of crisis (Civil War, WWI, etc.), and today. I hope that sounds like a good plan to you. If you have questions for Part II, please drop them below and I’ll incorporate them into my writing. Ok, onto the history…

The relationship between presidents and the press is a complicated one and has been since George Washington took the oath of office on April 30, 1789. Presidents need the press, in whatever form it takes, to make the most of their bully pulpit authority, yet the tradition of the fourth estate calls for the press to hold authority accountable. Let’s break down those ideas, where they came from, and what that looks like in American history.

The term “fourth estate” predates the United States and refers to a public press in Great Britain. The Oxford Dictionary loosely attributes the term to Edmund Burke, an eighteenth-century conservative philosopher and leader of the Whig Party. He may have used the term in debates on the floors of the Commons on February 19-20, 1771.

Edmund Burke

The concept of estates derives from Old World social structure. The first estate was the clergy; the second estate was the nobility; and the third estate was the commoners. The French ancient regime was organized around these estates and the British constitution loosely nods to it as well, though it evolved over time. The press as the “fourth estate” emerged in the eighteenth century alongside the rise of newspapers and widespread consumption of printed information.

The three estates in France

It was also made possible by the British constitutional system. The French monarchy was still absolute in the eighteenth-century and there was not much of an opposition party or opposition press advocating for specific policies. There were political cartoons that lampooned the king and queen, of course, but the weak legislature made real opposition politics challenging. I am oversimplifying here, and I am sure that French historians want to guillotine me, but my main point is that the political system did not produce the same sort of grounds for a fertile political press.

Across the English Channel, various reforms culminating in the Glorious Revolution reduced the power of the British monarchy and strengthened Parliament. In the eighteenth century, two parties battled for control: the Whigs and the Tories. Loosely speaking, the Tories were more conservative, more pro royal family, and considered the court party. The Whigs were more radical (relatively speaking), more critical of the royal family, and was referred to as the country party. Neither party was trying to destroy the British Empire or the British constitutional system, but rather pursue a specific direction—which is known as a loyal opposition.

The rise of two parties emboldened and supported a political press. Rather than annoying gnats to be crushed (though monarchs certainly tried), the fourth estate name bestows a certain nobility and honor to the profession. They have a purpose and a place within the system, and the system needs the fourth estate for balance. They hold power to account as part of the loyal opposition.

This concept was a new one. Absolute kings viewed opposition as inherently disloyal and even traitorous. This concept also serves as a key foundation for American politics. You can disagree with the president and the party in power and still be a loyal American. You can criticize people in power, either in a newspaper or a newer medium, and still be a loyal American.

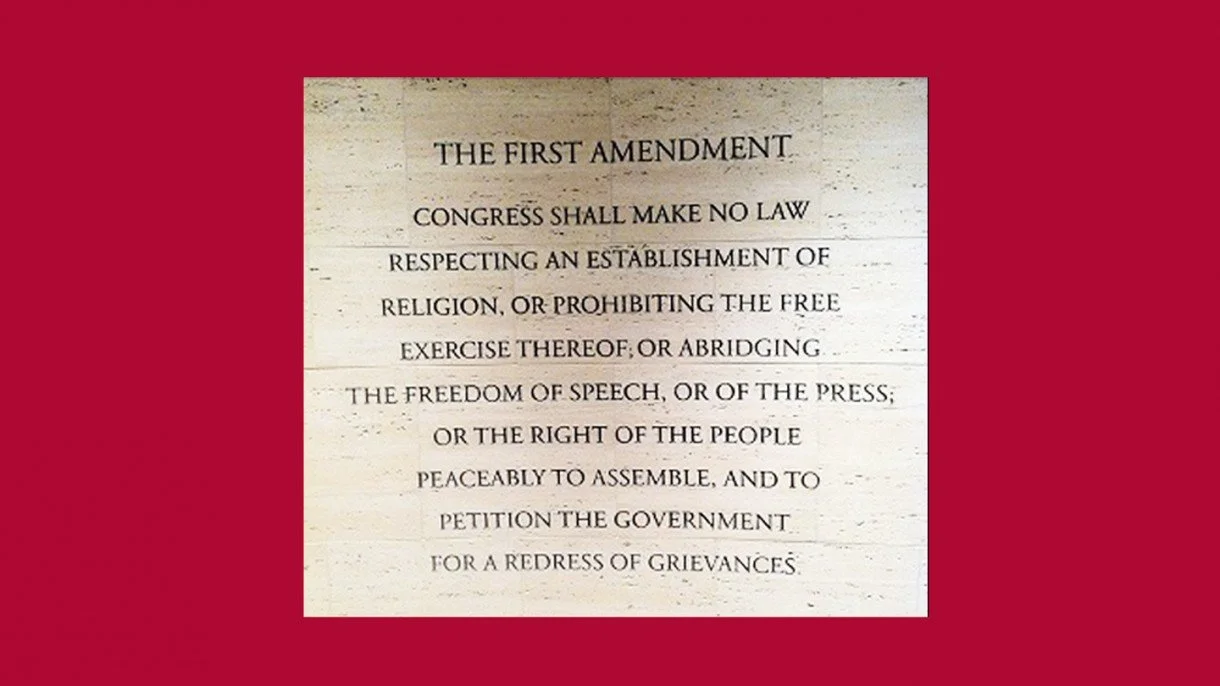

American colonists treasured this inheritance and considered it an essential part of their political world, first as colonists and then as citizens of the new United States. They enshrined this right into the First Amendment, which reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

I want to pause and dissect the amendment here, because I hear people discuss first amendment rights and get it wrong all the time. That amendment gives you the right to say terrible things about the government and still be protected from government retribution. It is designed to prevent against government crackdowns on speech, as absolute monarchs would have done in the eighteenth century. Two key caveats. 1) There are exceptions for speech designed to provoke violence, though these are narrowly tailored. 2) This amendment only applies to the government.

Let me repeat that for those in the back: THE FIRST AMENDMENT ONLY APPLIES TO THE GOVERNMENT. Private businesses and individuals are not obligated to respect your first amendment rights and there can be social consequences for your actions. People often say, “just because you have first amendment rights, doesn’t mean you don’t suffer consequences.” That is true if the person inflicting the consequences are your friends, family, coworkers, employers of a private business, or a privately-held social media company. It is not true of the government.

Now, just because it’s the law, doesn’t mean presidents have always liked it. From the beginning, most presidents have been annoyed by their press coverage. That is kind of the point.

In my first book, The Cabinet, I wrote about George Washington’s frustration with the press. He was a big fan of newspapers and subscribed to many, including The Aurora, a Democratic-Republican newspaper in Philadelphia. In 1793, The Aurora criticized the administration for refusing to help France in its war with Britain, and Washington canceled his subscription. The editor, Benjamin Franklin Bache, continued to deliver three copies of the newspaper to the President’s House every morning—just to annoy Washington.

And it worked. Washington vented and grumbled about Bache and the criticism in the newspapers in cabinet meetings. But he never said anything publicly because he believed it was beneath the dignity of the office to respond to the criticism. He also understood the power dynamic. The president was far more powerful than one lowly editor struggling to make a living; he would not punch down.

For much of the nineteenth century, newspapers were intensely partisan. As the parties evolved, there were Federalist and Democratic-Republican newspapers, then Democratic and Whig newspapers, and finally Democratic and Republican newspapers. A few newspapers tried to play it down the middle, especially if they relied on government printing contracts, but they were fewer in number.

Naturally, the opposition newspaper tormented presidents, while the loyal newspaper defended the administration. Depending on the president, sometimes the relationship was startlingly close. For example, when Andrew Jackson lived in the White House, he regularly crossed Pennsylvania Avenue to the Blair House to spend the evening with the Blair family.

Blair House

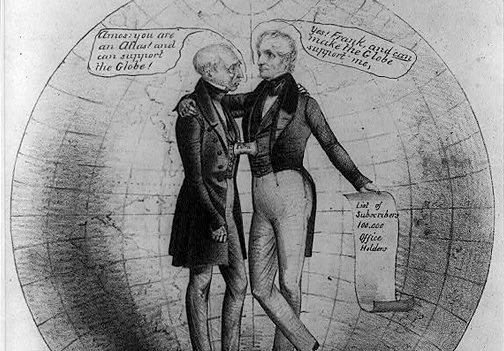

Francis Blair, Sr. was the Editor-in-Chief of the Washington Globe, the Democratic Party mouthpiece. After dinner, President Jackson and Blair sat by the fire and planned out the stories and headlines for the next day’s edition.

A cartoon depicting the close political relationship between Blair and Jackson

Few presidents were that cozy with their party’s paper, but they almost always had some sort of political relationship. Thurlow Weed’s Evening Journal in Albany, New York supported Whig candidates including William Henry Harrison, and then helped build the Republican Party. In the Log Cabin and then the New-York Tribune, Horace Greeley supported Harrison and then Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Newspaper editors often served as regional power brokers, especially in places like Illinois, Ohio, and New York. At the height of the spoils system (roughly 1840s-1883), presidents rewarded supporters with lucrative contracts and government positions. Sometimes newspaper editors received positions, but more often they helped dictate who received positions through their networks. The spoils system ended with the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act in 1883, which installed a merit-based system for most federal positions.

The president’s relationship with the press fundamentally changed at the end of the nineteenth century for two reasons. First, the rise of new technology made the president more available to the American people. Second, the arrival on the scene of the master of the bully pulpit, Theodore Roosevelt. We’ll pick up there soon.