The Justice Department Has Lost Its Way

A few weeks ago, news leaked that the Department of Justice had removed prohibitions designed to prevent election interference. Internal memos now permit “federal investigators…to take public investigative steps before the polls close, even if those actions risk affecting the outcome of the election.” These reports are particularly ominous, considering they come on the heels of Attorney General William Barr’s remarks that the Department of Justice would consider sedition charges against protestors, especially in Democratic cities. Federal authorities are currently adding a “non-scalable" fence around the White House, Lafayette Square, and the Ellipse - suggesting the president is planning to incite protests. Tensions over racial injustice, the Supreme Court, and the election results will continue to escalate for the next several weeks and Barr may have ample opportunity to act on his threat.

Sedition charges would return the DOJ to the darkest moments in its history. Starting in 1798, the federal government, and the Attorney General in particular, have occasionally targeted political dissidents for criminal prosecution. Each incident is a blight on the First Amendment and remembered by history as a betrayal of the principles contained in the Constitution. The DOJ was created to defend the rights of the most vulnerable Americans, not attack those that voice disagreement with the president.

In 1798, Federalists in Congress passed four bills known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The laws increased the naturalization time for immigrants, empowered the president to deport or arrest alien residents, and made it a crime for citizens to "print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous, and malicious writing" about the federal government. The bill targeted the Democratic-Republicans, who tended to enjoy more support among newly-immigrated Americans. The Adams administration then arrested and tried several prominent journalists and editors who had published material critical of the Adams administration. In 1800, popular outrage over the Alien and Sedition Acts fueled an overwhelming Democratic-Republican victory in both state and federal elections. After taking office, President Thomas Jefferson pardoned the individuals still serving jail sentences and allowed the sedition legislation to expire.

political cartoon depicting the Alien and Sedition Acts

Not all of Adams’s successors learned from the poor example set by the Federalists. During World War I, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer succumbed to congressional pressure to clamp down on political dissent. Justice Department officials conducted “Palmer Raids” in over thirty cities, arresting thousands of suspected radicals. Officials arrested the suspects, most of whom were alien residents, without proper warrants and held them for several months without trial.

Similar cases were brought against communists in the 1940s and 1950s, until the Supreme Court ruled in Yates v. United States that teaching ideals, no matter how unpopular, does not count as planning the overthrow of the government.

The DOJ has battled additional scandals in recent years, but the prosecution of sedition cases against political protestors are some of the worst betrayals by the DOJ. The position of the Attorney General was created to help the executive branch adhere to the principles of the Constitution. The scope of the position changed dramatically in 1870 when Congress created the Department of Justice to help the attorney general manage the federal government’s increasing caseload. But the Radical Republicans in Congress also hoped that a more robust DOJ would enforce Reconstruction and defend the rights of the most vulnerable citizens, not attack them.

In 1789, the First Federal Congress created the attorney general as part of the Federal Judiciary Act: “And there shall also be appointed a…person, learned in the law, to act as attorney-general for the United States…whose duty it shall be…to give his advice and opinion upon questions of law when required by the President of the United States, or when requested by the heads of any of the departments, touching any matters that may concern their departments.” Because the attorney general had no department over which to preside, the position often served as the legal advisor and constitutional guide for the executive branch.

Edmund Randolph, the first attorney general, welcomed these responsibilities. He frequently offered President George Washington counsel on legal, diplomatic, and domestic issues. For example, he questioned the legality of the First National Bank in 1791 and encouraged Washington to issue the first veto in 1792. The other department secretaries, including trained lawyers Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, also sought his input on issues that arose in their departments.

Randolph’s successors followed this model. As Jefferson and his cabinet considered the Louisiana Purchase, Attorney General Levi Lincoln advised the president on the legality of the purchase and the potential need for a constitutional amendment. In the summer of 1862, Attorney General Edward Bates enthusiastically supported the Emancipation Proclamation, regardless of his previous objections to gradual emancipation. Although he was among the more conservative members of Lincoln’s cabinet, his sons had enlisted in both Confederate and Union armies. Bates supported the proclamation, and all measures, that would hasten the end of the bloody Civil War.

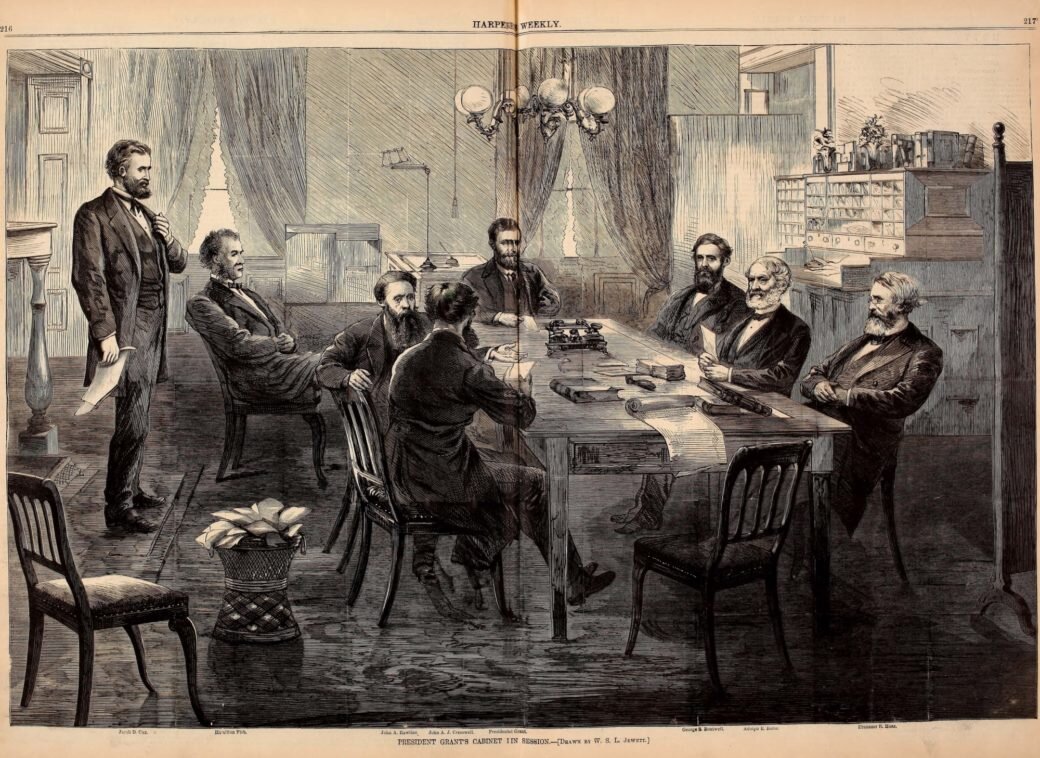

The first attorney general to oversee the new Department of Justice in 1870 made the most of this opportunity. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Amos T. Akerman as attorney general and Benjamin H. Bristow as solicitor general. Grant instructed Akerman and Bristow to prosecute individuals who committed crimes against African Americans under the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Both Akerman and Bristow were from the south and had witnessed firsthand the horrors of slavery and systematic racism. Along with Grant, they believed the powers of the DOJ provided an opportunity to boost the fledging citizenship rights and suffrage of black communities. While Grant was willing to send in federal troops to enforce the 14th and 15th amendments, the attorney general and solicitor general also used legal channels to challenge the newly-formed Ku Klux Klan.

Ulysses S. Grant’s cabinet

Since Grant’s presidency, many presidential administrations have welcomed the opportunity to use the DOJ to bolster citizenship and defend vulnerable communities. Attorney General Robert Kennedy promoted aggressive enforcement of civil rights, prosecuted cases to combat organized crime, improved legal access for the poor, and fought juvenile delinquency. For example, under Kennedy’s direction, the DOJ litigated 57 voting rights cases, opened several new polling booths in the south to serve black voters, and helped enforce school integration.

During President Barak Obama’s administration, Attorney General Loretta Lynch defended the rights of LGBTQ individuals and fought state legislation in North Carolina that restricted the use of bathrooms by transgender citizens.

Since Barr’s appointment in 2019, the DOJ has already sunk to new lows. For example, in early September, the Justice Department announced that it is seeking to assume the defense of President Donald Trump in a defamation suit brought by E. Jean Carroll, who has accused Trump of rape. While this argument is legally questionable, it is an inappropriate use of government resources.

But that insult would be nothing compared to the criminalization of protest. The DOJ’s involvement in sedition cases would be remembered alongside previous miscarriages of justice. Historical precedent demonstrates that the Department of Justice is a powerful tool to better the nation. We should expect the current DOJ to live up to this moral standard.